The events that happened are the past, but ‘history’ is the record of those events. The two are rarely identical. Our connection with history is mediated through the stories we hear and remember. These stories can be skewed, and there is nothing wrong with trying to bring them more in line with reality.

I experienced this tension recently when I finished John Grisham’s Camino Ghosts. I had started it last year but put it down, finding the story initially uncompelling. Last week, while browsing my Kindle, I realized I had never finished it. I gave it another chance because Grisham is a favorite author of mine; I love how he connects his stories with real-world situations, helping me see things in a different light.

I finished the book earlier today and found myself weeping at the end. Briefly, the story follows a writer documenting an island off the north Florida coast inhabited solely by descendants of former slaves. The last inhabitant, an 80-year-old woman, is fighting a ruthless casino developer who wants to take over the island. The story has a good ending, but I found myself reflecting on why it moved me so deeply.

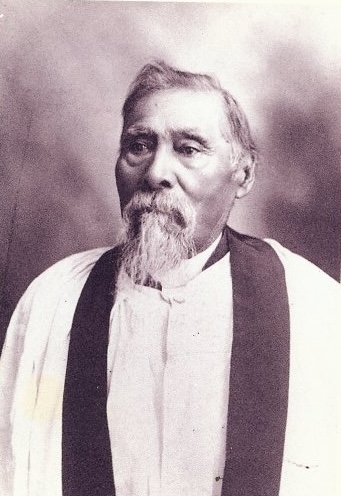

This reflection connected with another activity I’d been doing: genealogy. I decided this weekend to set aside time to look at my family tree, exploring the history of my great-great-great-grandfather, Rev. James Settee. I was researching his progenitors and came across an article written by Raymond Shirritt-Beaumont for a public school curriculum in Northern Manitoba. It discussed Rev. James Settee and his cousin — and later colleague — William Garrioch.

The author made a cryptic remark that a Joseph Smith was Settee’s great-grandfather. The article explored various possibilities before focusing on one person: a Joseph Smith who arrived in the Hudson Bay in the late 1700s. He made five journeys inland into what is now southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, primarily to connect First Nations people with the Hudson’s Bay Company for trade. Smith eventually died on one of these trips. Remarks in his boss’s journal seemed to imply he had a “local family.”

For those unfamiliar with this history, that was very common. European men often formed families with First Nations women. Their children are known today as the Métis or Country Born. The article speculates that this child was Rev. James Settee’s grandfather. There’s no concrete proof; it’s a historical speculation based on Settee’s own claim of a Smith ancestor. This is where the past and the record of it — history — diverge.

“Certainly the glimpse Settee gave us of life among the Swampy Cree in the early years of the nineteenth century reveals a culture in transition, a unique blend of aboriginal and European that defies easy definition. For the Garriochs and Settees, that cross-cultural exchange had been going on for four generations, and perhaps longer, when James Settee and William Garrioch set out in 1824 for the mission school at Red River. It continues today among their descendants; indeed, one might say that the family represents Canada in microcosm. From its multicultural beginnings, the Garrioch family has become a new people, one that is firmly planted on this continent, but with roots stretching out across the seas. When all is said and done, what could be more Canadian than that?”

[Raymond Shirritt-Beaumont, Wabowden: Mile 137 on the Hudson Bay Railway, (Frontier School Division, 2004), 129.]

It was with this understanding of my own ancestors’ blended history that I returned to the story of the island in Camino Ghosts. Reading the story of a woman whose ancestors were slaves, who grew up on the fringes, and who finally saw justice done connected me directly to the story of the First Nations and Métis people of Canada — my ancestors. Reading how they worked not only in the fur trade but also in spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ throughout Manitoba and Saskatchewan connected me personally.

I am a long time removed from that period. Yet, thinking about their journeys through the wilderness of Northern Canada brought me back to my own experiences in that same wild. As I read, pictures of the lakes, trees, animals, and fish came directly to my mind.

The story became profoundly meaningful because I could feel a direct connection. Through my ancestors, their stories — the injustices they experienced through displacement and cultural pressure and the hardships they endured — became real. The theme of justice in Grisham’s book resonated with that personal history.

This reminds me again of the importance of relationship. It is impossible for me to care about the world or to desire to make it a better place without a relationship with it. That’s why perspectives are important. I must expose myself to other people’s perspectives — to understand their point of view, to hear their stories of joy, hardship, and justice. It is only through hearing these stories that we can connect our stories together.

I’ll close with a moment from the show Alone. In Season 10, set at Reindeer Lake, the producers invited Cree elders from the Peter Ballantyne Cree Nation to give a blessing. An elder stood and prayed over them in nîhithawîwin — the subtitle translation was the words of the Lord’s Prayer. This prayer had become so integral to this First Nations community’s way of life that their blessing invoked a connection with the God of Jesus.

I connect directly back to that because it was my great-great-great-grandfather, Rev. James Settee, a missionary with the Church Missionary Society in Northern Saskatchewan, who worked at making that prayer meaningful for First Nations peoples as he planted churches and communities of Jesus-followers in that part of the world. It felt like a full circle moment — a story connecting past to present, and history to the heart. This reveals what Shirritt-Beaumont so ably stated above, “a unique blend of aboriginal and European that defies easy definition.”

These are the connections have I found, but every story depends upon its listener. What’s your perspective? How do you connect with the world around you in a deeper way? How does your family story impact your experience so that you too can weep — like me — when you see beauty? If that is a new idea for you, what’s the first step towards discovery?

Photo of Rev. James Settee from the The Cathedral Church of St. John Archives.